Reserve Bank of Australia governor, Phillip Lowe surprised markets at the October board meeting with a dovish statement, and an underwhelming 0.25% rate hike. Governor Lowe noted that while inflation pressures continue to be an issue in Australia, they are not as acute as in other global markets. Wages aren’t rising nearly as quickly, and consumers are more sensitive to rate rises due to large housing debt that is predominantly on variable interest rates. This has led to expectations that the RBA’s rates will peak at lower levels than in other developed markets. Is this true, or is the RBA making a mistake by taking its foot off the rate rising pedal too soon?

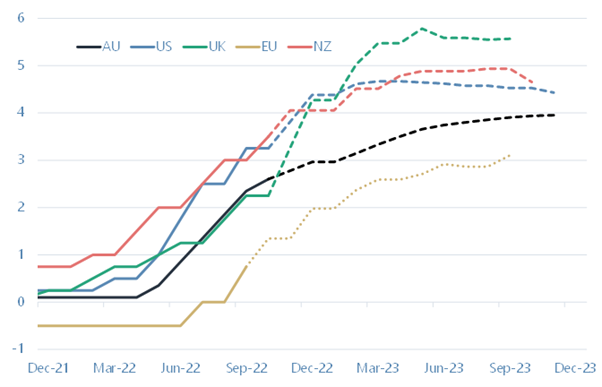

Market pricing for terminal rates

Source: Bloomberg

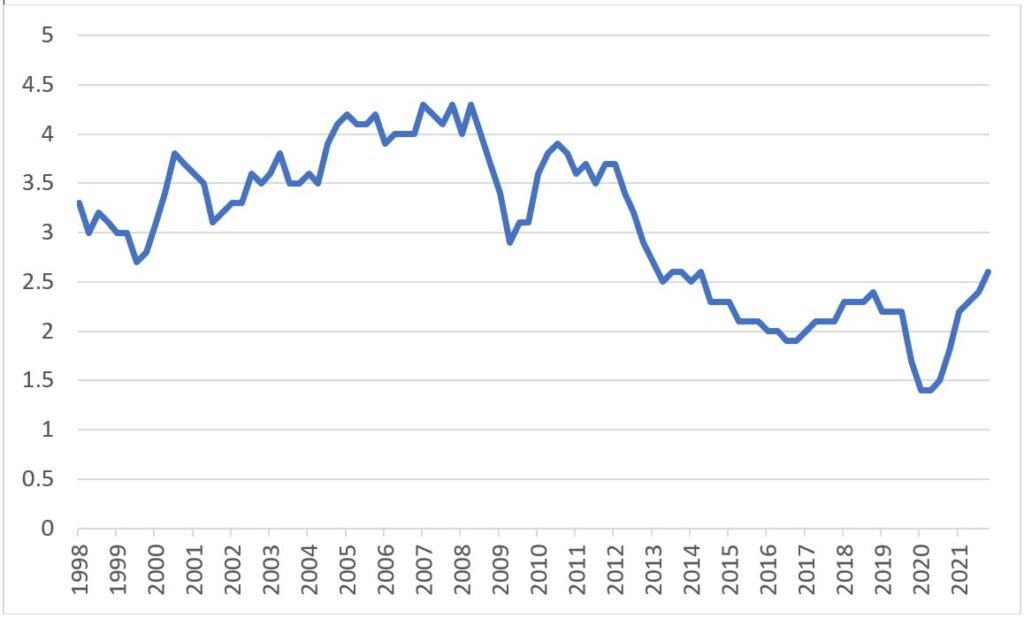

Wage rises have been a key focus for the RBA as labour markets have tightened after ten years of relatively benign wage growth. The sharp decrease in unemployment, to 50-year lows has given the RBA a chance to try to achieve more substantial wage growth, but so far they have been disappointed. With wages growing by 2.6% in Australia you could be forgiven for agreeing with the RBA in slowing rate rises, to keep labour markets tight and to try and stimulate more substantial wage growth. However, this approach has some big flaws.

Australia Wage Cost Hourly Rates of Pay Ex Bonuses YoY

Source: Bloomberg, ABS

Firstly, Australia releases data infrequently which means in times of high volatility we get very lagged insights; the most recent Australian wage data period started over 6 months ago.

Secondly, the Australia labour market is heavily unionised and driven by minimum wage and collective agreements which take time to renew. Over 20% of wages are set by the award (minimum) wage, while a further 35% are set by enterprise bargaining agreements which renew every three years. In 2022 the Fair Work Commission set the yearly award wage increase at 5.2%, the largest increase since 2006 and twice the previous years. Milford visits hundreds of companies every year and one of the most common issues management teams raise is how difficult it is to get staff, while having to pay significantly higher wages to secure talent.

So, it is unclear if wage growth is in fact benign as the RBA suggests, or simply yet to be seen in the data.

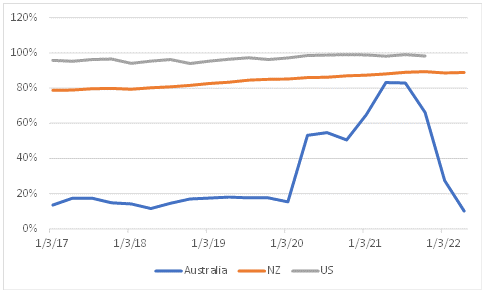

Australia has one of the most sensitive housing markets to moves in interest rates among developed nations, because of the large proportion of floating rate borrowers. On average about 30% of Australian mortgages are fixed while the remainder are variable, compared to 85% fixed in NZ and almost entirely fixed in the US. Australian fixed mortgages have an average duration of about two years, compared with NZ at one and a half years and the US at 27 years. Mortgage rates in the US are set off the 30-year government bond, while in NZ and Australia, banks set mortgage rates off short-term bank bills which have a much higher correlation to the official cash rate. This dynamic means that any rises in central bank rates will be passed through to mortgage holders quicker in Australia, than in other nations. The RBA has concluded that rates won’t need to go as high in Australia, because mortgage payments will rise rapidly leading to falls in consumption spending. This compares to the US where business investment needs to be reduced to a level where job losses cause a drop in spending, which is generally a slower process.

Share of new mortgages with fixed rates

Source: RBNZ, RBA, FHFA

In summary, the RBA views Australia as a market where rates won’t need to go as high as other countries because of lower wage inflation, and a quicker mechanism to pass through rate rises via housing. If they are wrong and indeed Australia is not that different to other countries, they may end up having to chase the pack, and ultimately raise rates even further and faster.