Since OpenAI released ChatGPT to the public in November 2022, generative AI has taken the investing world by storm. Any company that is even tangentially related to AI (generative or not) has likely seen its stock price bid up aggressively as investors take a “shoot first and ask questions later” approach to this transformative technology. But, as with all technological paradigm shifts, investors need to formulate a framework for thinking about the emerging technology lest they become caught up in the frenzy.

Having returned from a recent technology research trip to the US, my observations are 1) the hype around generative AI has subsided somewhat compared to three months ago when my colleague Kyle Twomey was there on a similar research trip, and 2) many investors still do not have an AI investment framework beyond chasing AI momentum stocks. We do not believe generative AI is a bubble – after all, humans have been working on AI systems since the 1950s, but only very recently has compute, bandwidth and data become sufficient to make transformational breakthroughs. However, the uncertainty around timing and quantum of any financial upside, paired with technology and semiconductor stock prices that have rallied sharply year-to-date, (Nasdaq 100 up 40% YTD compared to 14% for the MSCI World Index) means investors need to be particularly careful with stock selection within this theme.

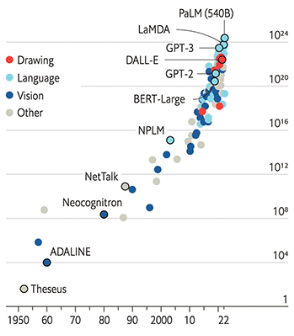

Chart 1: Estimated computing resources used for model training, in FLOPS (Floating-point operations per second)

Source: “Compute trends across three eras of machine learning” – J. Sevilla et al, arXiv 2022

So, what factors should investors consider?

The enablers have already bolted

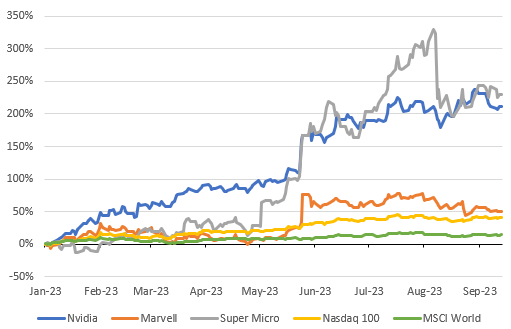

The near-term enablers of generative AI, especially the GPU (graphics processing unit), networking, and AI server vendors such as Nvidia, Marvell and Super Micro Computer, have likely priced in significant upside from the generative AI opportunity. These companies are pivotal to the initial buildout of AI training infrastructure over the near term but lack long-duration, recurring revenue streams and are historically highly cyclical. While generative AI might prove so transformative that “this time is different”, we consider it imprudent to chase these stocks higher.

Chart 2: YTD returns of several AI infrastructure enablers

Source: Bloomberg

The open question with respect to this AI infrastructure buildout is the payback or return on investment. OpenAI, which operates by far the most popular consumer chatbot (ChatGPT) and by far the most widely used developer plugins, is on pace to exceed $1bn revenue over the next 12 months. We might reasonably assume total generative AI industry revenue is in the low single-digital billions, considering most listed software and cloud companies aren’t even willing to speculate on AI revenue timing. Wall Street estimates Nvidia will sell over $40bn of AI chips this year, rising to $65bn next year and nearly $80bn the following year. We would need to assume staggering compound annual growth rates for AI revenue to deliver any kind of acceptable return on these massive upfront infrastructure investments, bearing in mind that Nvidia chips are the largest but not the only component of AI data centre costs.

What is the moat?

Sequoia Capital, a prominent VC firm, said at a recent conference that a year ago it felt like OpenAI had an insurmountable technical moat and now that moat is gone. While OpenAI’s GPT-4 is inarguably the most capable foundation model available today, rumours suggest Google’s Gemini model (currently in training) will blow it out of the water. Once GPT-5 is released, OpenAI likely retakes the crown, at least until Google’s next model. This is to say that the leading foundation models are increasingly undifferentiated from a capability standpoint.

Given how quickly generative AI (and AI generally) is advancing, technical moats tend to be overstated and are only useful to the extent they can manifest into a distribution moat. The question investors should ask is not “does company X have the best (AI) tech?” but rather “has company X become the default?”.

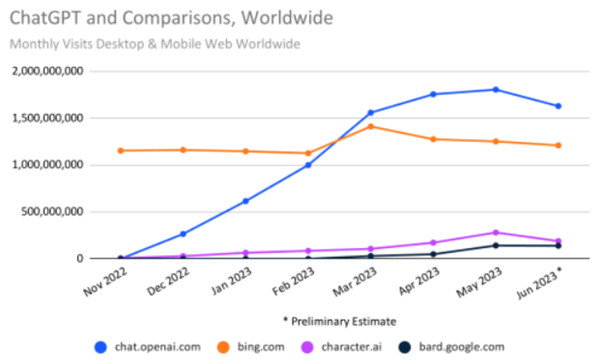

Fortunately for OpenAI (and its largest benefactor Microsoft), its first-mover advantage has allowed ChatGPT to become the default for consumers and the OpenAI API (Application Programming Interface) to become default for developers.

Investors should be sceptical of any company that claims to have the best generative AI tech, models, features or capabilities, especially over the foreseeable future where most companies are just putting wrappers around an OpenAI foundation model.

Chart 3: ChatGPT website (chat.openai.com) visits vs other AI chatbots

Source: Similarweb

One additional point is that the claim that proprietary data is the moat and the key to fine-tuning existing foundation models may be overstated. While every company has proprietary data, not all proprietary data are high-quality enough to fine-tune a foundation model, not all data are cleaned and stored in a readily ingestible format, and almost all data are governed by contracts and user licences that may restrict how said data may be used by the company.

How to monetise generative AI?

The question of monetisation still appears to be largely unsettled. The companies on my research trip could be divided into two broad groups – one of mainly large incumbent companies with broad distribution that plan to explicitly charge for (generative) AI features or tools, and another of smaller companies that plan to provide AI functionality for free as part of a freemium model. Few companies have been as explicit or confident as Microsoft when it comes to pricing, which several months ago announced $30/month pricing for its Microsoft 365 Copilot before the product even went into testing.

Given how commoditised the average generative AI chatbot or assistant is likely to be – after all, if most are using the same 1 to 3 foundation models, how differentiated can they be? – it is hard for the team at Milford to see how the average company can sustainably charge for what will be a commoditised AI feature. There are, of course, some advantaged businesses in the Milford portfolios that will be able to sustainably monetise generative AI, either directly because of the type of service they provide (Nice Ltd), or indirectly because they are empowered platforms that don’t have to sell AI to customers (Meta Platforms).

Incumbents vs disruptors

Substantially all changes in industry structure boil down to a simple question: can incumbents innovate faster than disruptors can build distribution? Where the answer is no, an industry or subset of companies gets disrupted. What makes generative AI interesting is that the disruptive force behind this transformative theme sits not with some unique or proprietary technology built by a startup, but rather with OpenAI or another foundation model or even an open-source model – all of which are available to incumbents as well. To the extent the best innovation is wrapping a product or feature around a widely available foundation model, the incumbents should almost always win. The points above on distribution and monetisation further favour the incumbents.

My research trip was targeted at public companies, so there could be more interesting things happening at private startups, but on the public side it felt like companies were yet to come up with more compelling use cases and business models than AI chatbots/assistants/copilots on subscription/freemium which largely involve paying the OpenAI tax for what will become commoditised features. It feels like we are still far away from AI enabling something truly revolutionary – whether in terms of products, services, or business models. Generative AI in the digital realm is transformative, but likely needs to cross into the physical world to be revolutionary. On this front, perhaps only Tesla is seriously tackling the mother of all AI projects – real world autonomy.